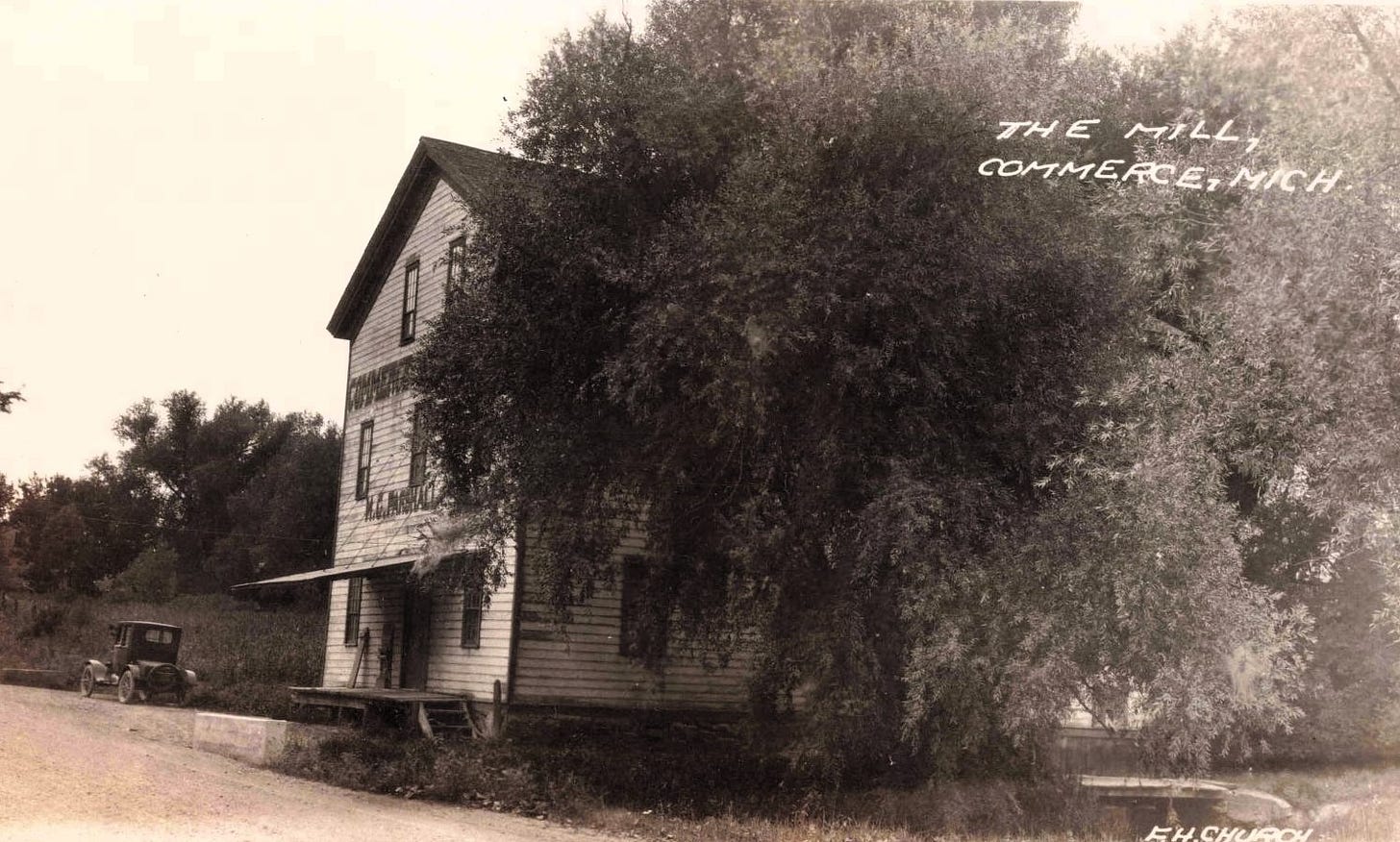

Long before Commerce Township had paved roads or zoning maps, it had a mill. Built in 1837, the Commerce Roller Mill stood along the Huron River and did one essential thing very well: it turned farm output into usable food. For nearly ninety years, that was enough to make it one of the most important places in western Oakland County.

This was not a side business or a picturesque extra. It was infrastructure.

Built for Water, Built for Work

The mill was constructed by Amasa Andrews and brothers Joseph and Asa Farr at a spot chosen for function, not scenery. The Huron River provided steady water power, and the mill’s undershot water wheel captured the river’s current without the need for a large dam.

Water was guided through a mill race and a flume, carefully controlled to keep the machinery turning. This system allowed the mill to operate through most of the year, a necessity in an agricultural economy where timing mattered. Grain waited for no one, and neither did livestock feed.

A Place Farmers Could Not Avoid

For farmers across western Oakland County, the Commerce Roller Mill was unavoidable. Wheat had little value until it was ground into flour. Livestock require ground feed. Farmers hauled grain by wagon, waited their turn, and settled accounts on the spot.

Cash was often scarce. Payment was often made through toll milling, in which the miller kept a portion of the finished product. This arrangement tied the mill directly into the rhythms of farm life. When the mill was busy, the township was busy. When it stopped, everything slowed.

More Than a Building

Throughout the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth century, the mill served as Commerce Township’s commercial center. News passed through. Deals were struck. Schedules adjusted around its operation.

Ownership changed as the years passed. Around 1900, the mill was owned by Milton Parshall. By the 1920s, Isaac Lutz had taken over the operation. These transitions reflected a broader reality: the business was durable but not immune to change.

When Progress Moved On

By the early 1900s, milling technology and food distribution were shifting rapidly. Larger mills, rail transport, and packaged flour reduced the need for small, local operations. Efficiency improved, but distance increased.

In 1927, after ninety years of service, the Commerce Roller Mill closed. It was not dramatic. There were no grand announcements. It simply stopped being necessary as it once had been.

Fire and Absence

In 1939, fire destroyed the mill buildings. Wood burned. Machinery warped. What remained were the parts that could not be consumed by flames: stone foundations, excavated channels, and the reshaped earth that once directed water toward work.

Those remnants still trace the outline of the operation. You can see where the river was diverted, where power was gathered, and where it was returned downstream.

Remembering What Fed a Township

In 1984, the site was developed as an interpretive historic area. Visitors today do not see a mill rising above the riverbank. Instead, they encounter absence made meaningful.