On an ordinary weekday in 1910, nothing remarkable happened in Belleville.

That is exactly why the day matters.

The morning began with sound. A train whistle carried across town as the Wabash line pulled into the depot. Mail sacks came off first. Newspapers followed. Freight after that. Belleville residents measured time by these arrivals. The train did not just bring goods. It brought news, prices, and proof that the town was part of a larger system.

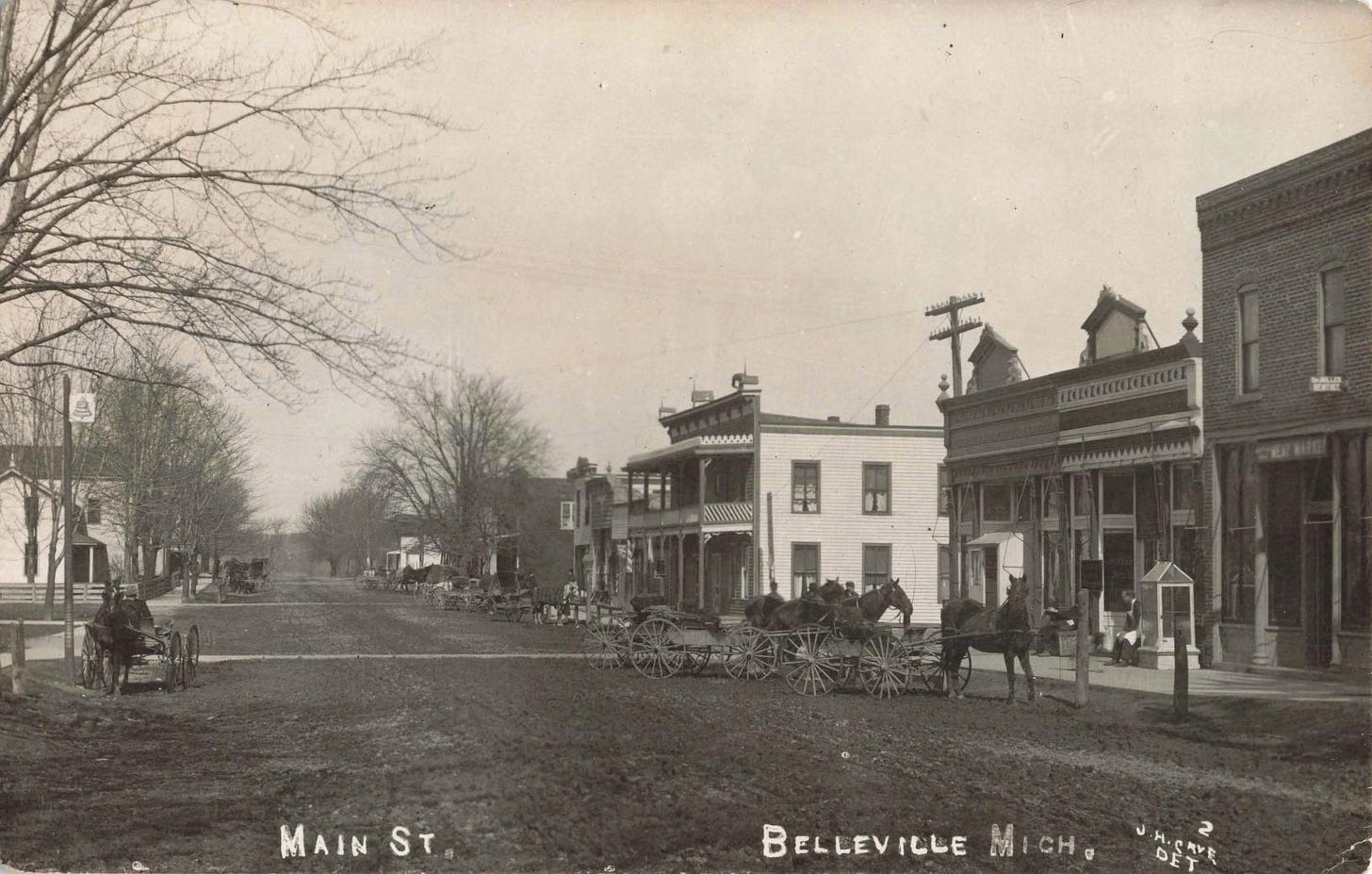

After breakfast, people moved toward Main Street. Storefronts opened on schedule. Clerks swept sidewalks. Wagons lined the curb. The Mandt Hotel already had activity inside—salesmen checking out, farmers meeting buyers, coffee poured for both. Hotels were not a luxury in towns like Belleville. They were working spaces where business and planning happened face-to-face.

By midmorning, the mill down by the river was busy. Grain arrived by wagon and left as flour or feed. The river powered the work, steady and mechanical. When the White mill ran, the town moved faster. When it paused, everything slowed. This rhythm shaped the day more than any clock on the wall.

At the same time, school was in session. Children filled classrooms, learning reading, arithmetic, and order. Few would go on to higher education, but that was not the goal. The goal was preparation—how to keep accounts, read contracts, and function in a world that expected reliability. Teachers lived nearby. The school bell marked time as clearly as the train whistle.

By afternoon, activity shifted again. The bank saw deposits and payments. Money moved carefully. Brick walls and ledgers signaled confidence. Belleville was not guessing about its future. It was planned for in small, cautious steps.

Evening did not bring quiet. Hotel porches filled with conversation. Meetings took place upstairs in civic buildings and lodges. Roads, bridges, and local improvements were debated. Entertainment came from participation, not performance. People knew one another. Decisions were made in person.

Here is the part that often surprises modern readers: life in Belleville in 1910 was busy. Structured. Demanding. Many residents today live farther from daily schedules than their counterparts did more than a century ago.

The ordinary weekday mattered because it repeated. One day looked much like the next. That consistency built trust, habits, and stability. When change came later—when the river was dammed and Belleville Lake reshaped the area—the town absorbed it because the foundation was already there.

History is often told through turning points. Belleville’s story is better understood through repetition. The town was built not by dramatic moments, but by ordinary days that worked.