The island people used, not just visited

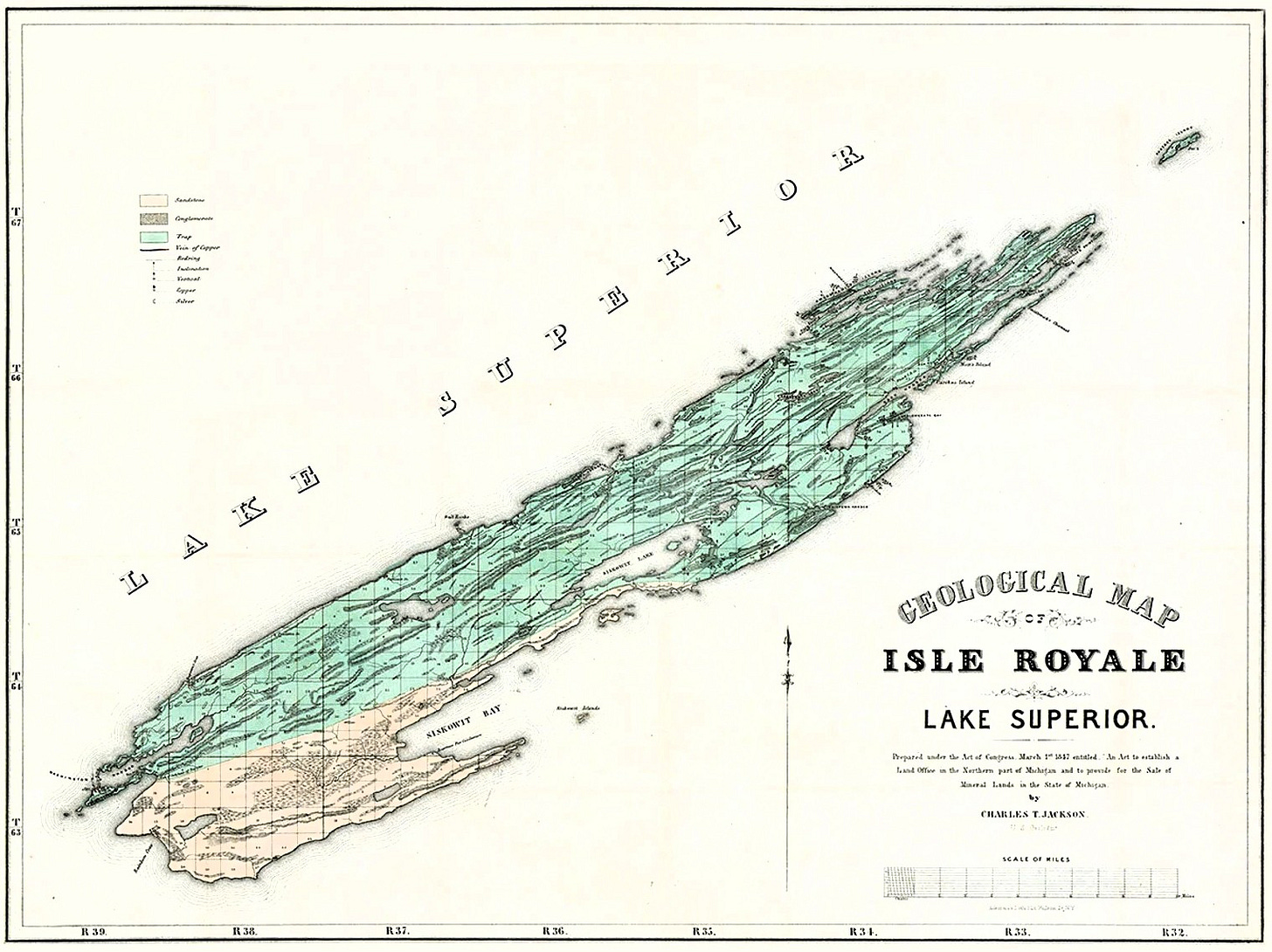

The History of Isle Royale, Michigan, is often told as a wilderness story. That is only half true. From the 1830s through 1940, Isle Royale was shaped by work and movement: copper prospects, commercial fishing, navigation lights, and a summer lodging economy built around docks and protected harbors.

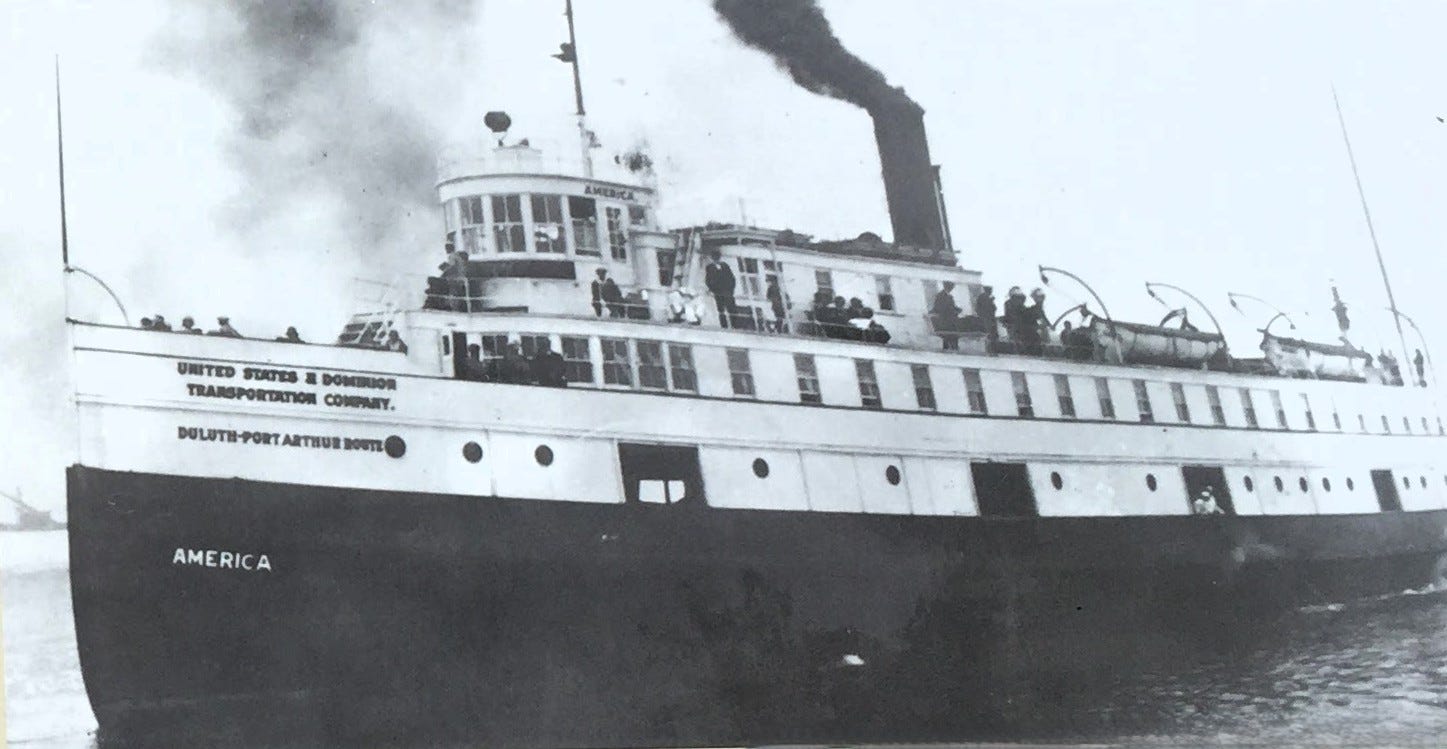

What made the island different was not size alone. It was a distance. On Isle Royale, the shoreline was the road. If you wanted supplies, you needed a ship. If you wanted visitors, you needed a dock. If you wanted ships to arrive safely, you needed lights.

1842–1859: Copper pressure and a need for safe harbors

After the 1842 Treaty of La Pointe opened the region to mineral entry, Isle Royale drew outside interest in copper. The National Park Service reports that by 1847, more than a dozen mining companies had established sites on the island.

Not every claim succeeded. But even short-lived mining created supply traffic and shoreline infrastructure. Ships brought people, food, equipment, and mail. In rough water, a harbor could mean profit—or survival.

Fun Fact About Isle Royale

Isle Royale and the Keweenaw Peninsula share the same copper-bearing rift geology. The National Park Service calls it a “distinctive copper-rich geology,” and USGS mapping shows the same major rock units tied to native copper in the region. But modern park geology summaries note a key difference: unlike the Keweenaw’s famous lodes, Isle Royale does not have abundant copper deposits or large lode bodies. Copper is present and widespread, yet the island never produced the kind of mining boom that would have covered its shore with mills, tailings, and company towns.