On the south shore of Houghton Lake, Prudenville did not grow because of railroads, factories, or corporate offices.

It grew because people wanted to catch fish.

That may sound simple. It is not.

The story of Prudenville, Michigan, shows how hunting, fishing, and outdoor recreation became the economic backbone of many small towns across northern Michigan — and why that model still holds today.

When the Lumber Was Gone, What Was Left?

Like much of Roscommon County, Prudenville began in the lumber era. Timber crews cut white pine and hardwood forests in the late 1800s. Sawmills operated. Camps thrived.

Then the trees thinned.

Across northern Michigan, that moment was decisive. Some towns faded into memory. Others adjusted. Prudenville made a hard pivot — from extraction to recreation.

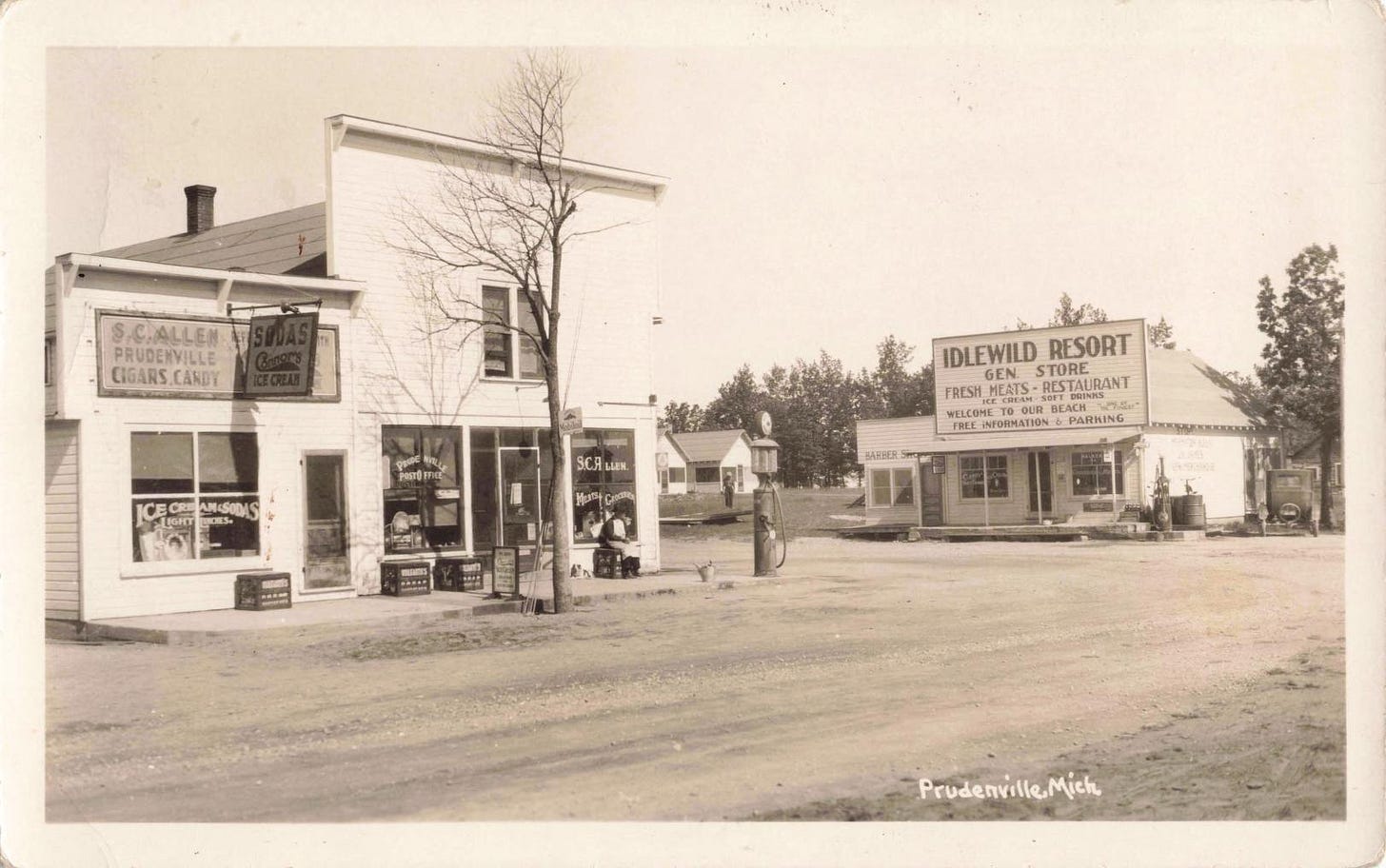

Instead of shipping lumber out, it invited visitors in.

The Lake Became the Industry

Houghton Lake is Michigan’s largest inland lake. By the 1920s and 1930s, it was already drawing anglers from Detroit, Lansing, and Saginaw.

Fishing was not a hobbyist’s pastime. It was commerce.

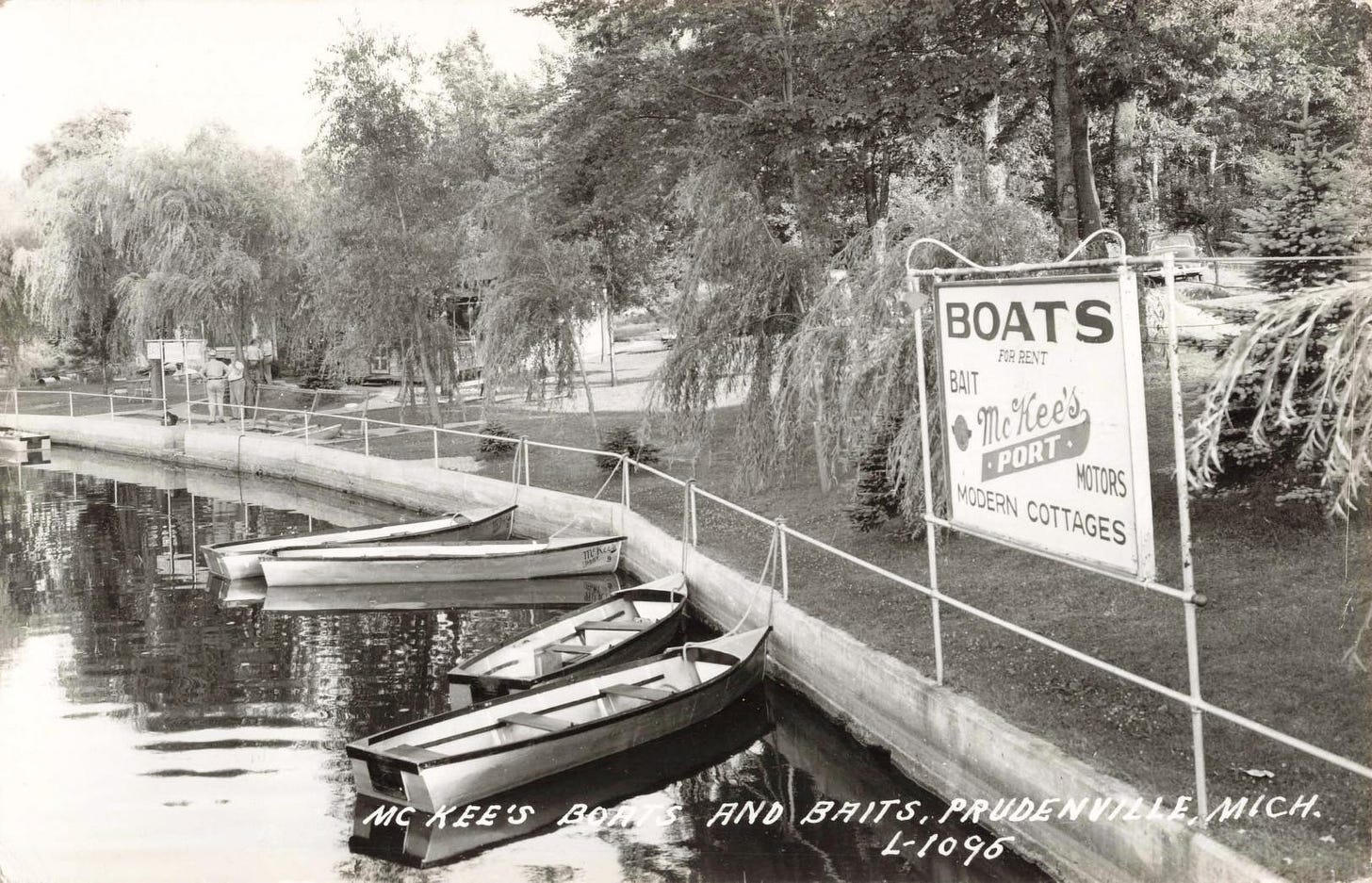

Bait shops lined the road. Rowboats waited at wooden docks. Businesses like McKee’s Boats and Baits did steady trade. Pike and perch filled coolers — and cash registers.

Every fish pulled from the water supported something on Main Street: groceries, hardware, gas pumps, soda fountains.

Outdoor recreation became infrastructure.

Cabins, Not Hotels

Prudenville did not build grand resorts. It built cabins.

Rows of small cottages appeared beneath the pines. They were practical and affordable. Families drove north, unpacked for a week, fished at dawn, and cooked at dusk.

Cabin courts allowed the town to expand seasonally without becoming urban. Summers brought crowds. Winters brought quiet. That rhythm defined the economy.

In the 1930s, Prudenville could generate more concentrated business activity in July than some agricultural towns saw all year. The summer surge was intense.

And it was predictable.

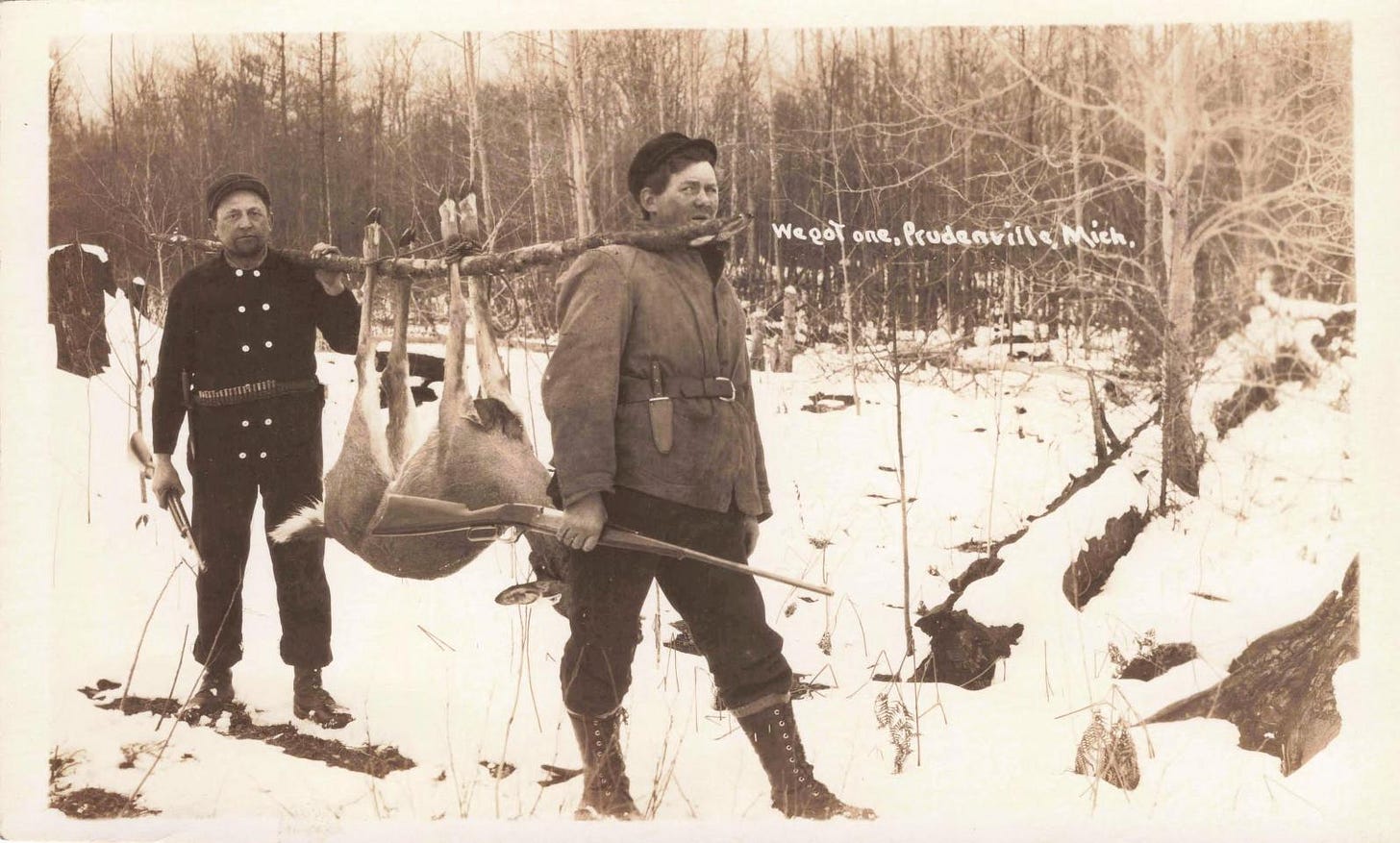

Deer Season Was an Economic Event

Fishing filled summer.

Hunting filled fall.

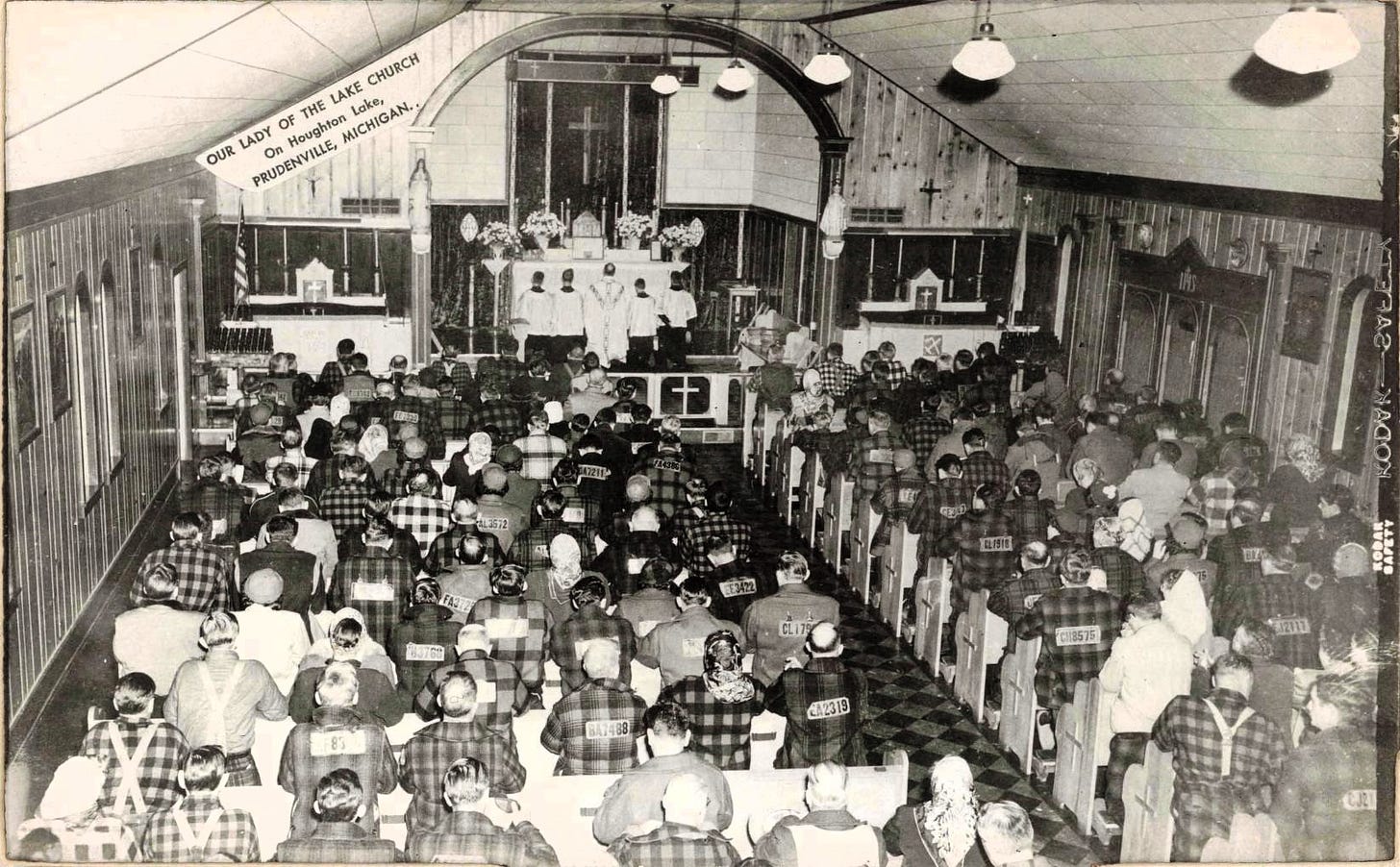

Photographs from the era show hunters kneeling at Our Lady of the Lake Church in plaid jackets, license numbers pinned to their backs. After Mass, they headed straight into the woods.

That image captures something essential.

Deer season was not just tradition. It was commerce. Gas stations stayed busy. Restaurants opened early. Ammunition, wool coats, and hot coffee sold fast.

The woods drove payroll.

In northern Michigan, hunting licenses and fishing permits have long been quiet revenue engines. They fund conservation. They support small businesses. They sustain rural tax bases.

Recreation Shaped Social Life

Outdoor recreation did more than pay bills. It shaped culture.

Johnson’s Rustic Dance Palace stood in the woods near Houghton Lake. On summer nights, music carried through open doors. Tourists and locals met there. Courtships began. Stories were shared.

The dance hall, the bait shop, the church pew during deer season — these places tied recreation to community identity.

That blending of visitor and resident is often overlooked. Prudenville was not simply a resort. It was a working town whose work happened to revolve around leisure.

The North’s Economic Blueprint

Prudenville’s model became common across the Upper Great Lakes.

When timber declined, northern communities leaned on what remained: water, woods, wildlife. Outdoor recreation replaced heavy industry as the primary draw.

Transportation reinforced that shift. Automobiles poured north by the 1930s. Greyhound buses stopped in town. Access kept the dollars flowing.

And that pattern persists.

Today, debates over tourism pressure, conservation policy, and development fill public meetings. Yet the foundation remains clear. Boat launches, marinas, deer camps, snowmobile trails — these are not side attractions. They are economic pillars.

Without hunting and fishing, towns like Prudenville would look very different.

A Small Town Built on Big Water

Prudenville never became a city. It did not need to.

Its strength came from seasonal waves of people who returned year after year. Grandparents brought grandchildren. Families rented the same cabins. Deer camps became generational rituals.

The factories never arrived. The rail hubs never formed. But the boats still line the shore each summer. Traffic still slows during the opening day of deer season.

In northern Michigan, outdoor recreation is not a lifestyle accessory. It is payroll. It is stability. It is identity.

Prudenville’s story proves a simple, provocative point:

Sometimes the most durable economy is built on a lake, a rifle season, and a steady line at the bait counter.

And for many small towns in the north, that formula still works.