The Lost Industries of Small-Town America

What Michigan’s Forgotten Factories Still Teach Us

Drive almost any two-lane highway in the Midwest, and you will see it: a grain elevator no longer taking deliveries, a brick factory with its windows knocked out, a rail spur that leads nowhere. These are not rare sights. They are common markers of how the American economy once worked—and how it changed.

Small towns were built around industries that made sense at the time. Timber, salt, agriculture, and manufacturing. Those industries created jobs, schools, churches, and local wealth. When markets shifted, transportation changed, or technology advanced, many of those industries disappeared. What followed was not just economic loss, but a long period of adjustment that still shapes these communities today.

Michigan’s Thumb region provides a clear and well-documented example of this national pattern. Its towns experienced rapid growth, sudden decline, and, in some cases, reinvention. The story is not about nostalgia. It is about understanding what actually sustains a community when its economic foundation gives way.

Boomtown Logic: Why Single Industries Took Over

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, specialization made sense. Transportation was limited. Supply chains were short. Towns formed where resources were abundant and access to rail or water was available. If a place had timber, it was logged. If it had brine, it made salt. If the soil and climate allowed, it grew a cash crop.

This approach produced fast growth. It also created fragile local economies.

When an industry thrived, everything revolved around it. Housing, stores, and even local government budgets depended on a single payroll. That concentration worked as long as demand stayed strong. When it did not, the damage was immediate.

Lesson One: Specialization Creates Risk

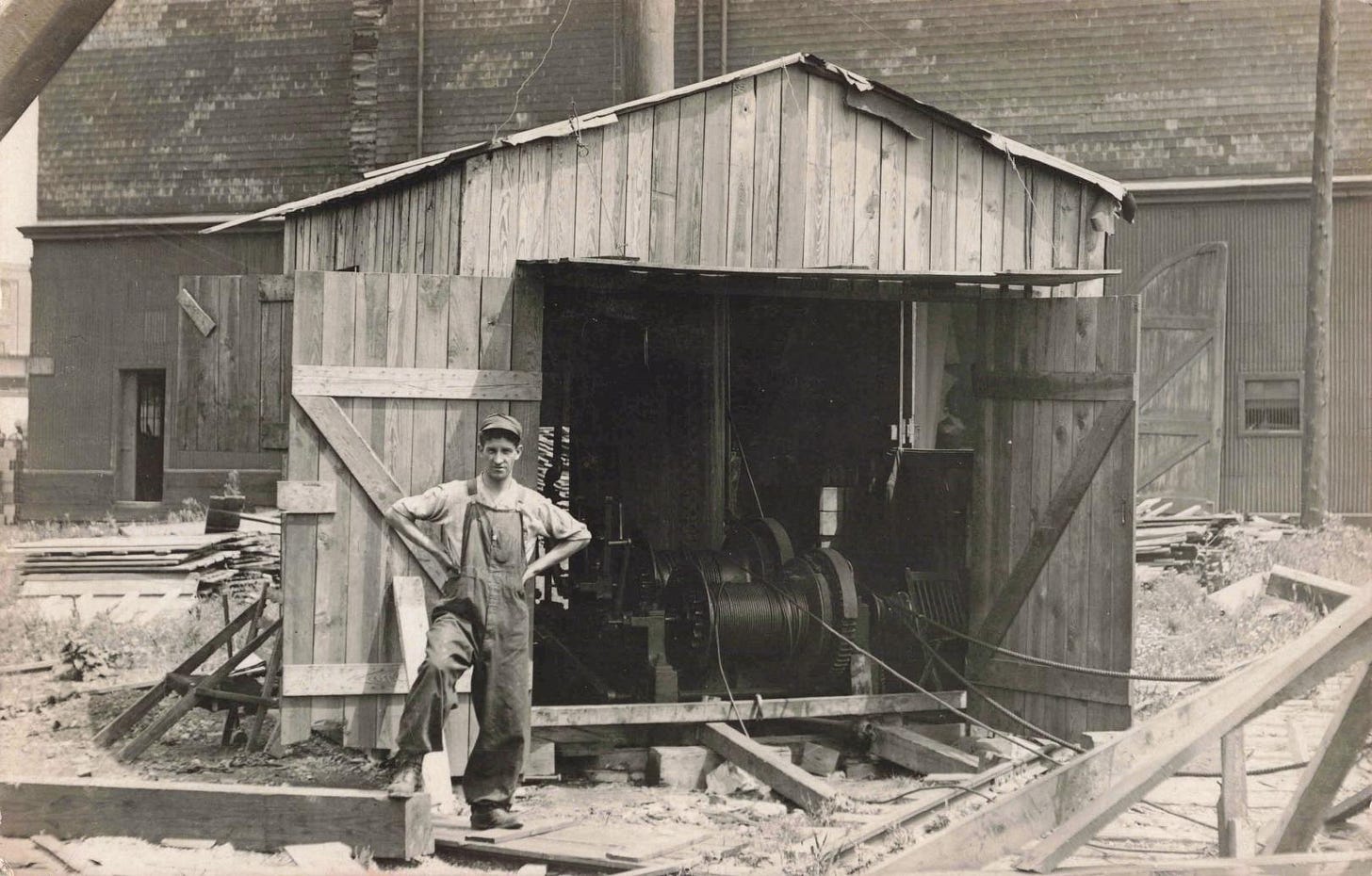

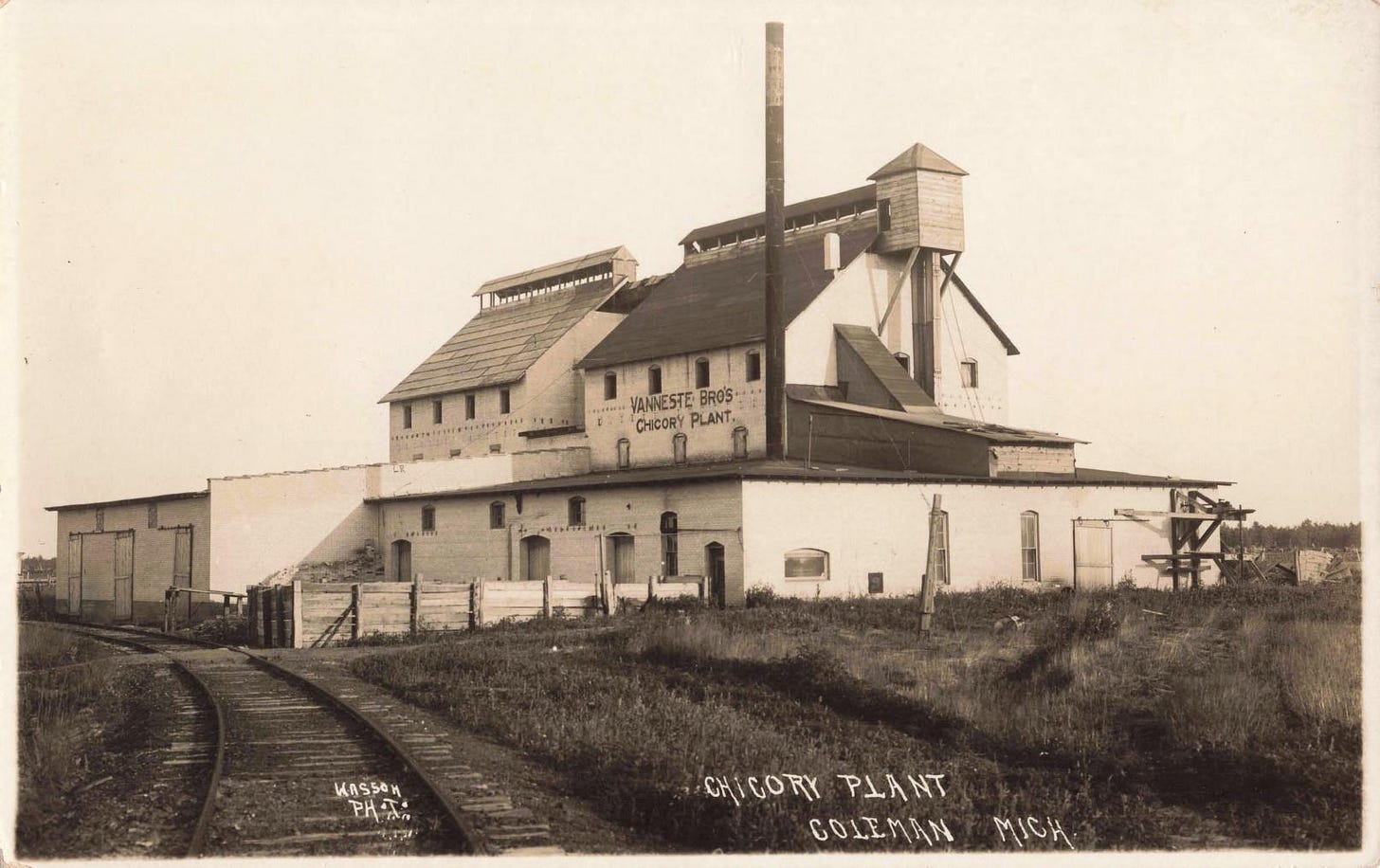

Michigan’s Chicory Industry (1860–1940)

Chicory is now a footnote in American food history, but for decades, it was a profitable crop. Used as a coffee substitute or additive, chicory found a ready market during periods of scarcity and high coffee prices. Michigan farmers took advantage of favorable conditions and turned what many considered a weed into a commercial product.

Processing plants followed. Jobs followed. Towns adjusted their local economies to serve that market.

Then tastes changed. Imports increased. Coffee became cheaper and easier to obtain. Chicory demand collapsed. Fields were replanted. Factories closed.

What made chicory valuable also made it vulnerable. It existed because of a specific market condition. When that condition ended, the industry vanished.

Related reading:

History of Michigan Chicory Production – From Ditch Weed to Coffee’s Breakfast Sidekick (1860–1940)

Salt and the Fishing Economy

Salt built more than just curing sheds. It supported the Great Lakes fishing industry by enabling large-scale preservation. Michigan’s deep brine wells enabled the cheap, large-scale production of salt. Fishing fleets relied on it. Entire towns depended on the trade.

The decline did not come from resource depletion. It came from innovation elsewhere. Refrigeration improved. Transportation networks expanded. Fish could be shipped fresh. Salt-based preservation lost its edge.

Salt works are closed. Fishing operations consolidated. Jobs left.

Related reading:

Michigan Salt Industry History – 1800s Thumb Production, Decline & What Remains Today

Key point: Specialization rewards towns quickly but leaves little margin for error.

Lesson Two: Reinvention Is Hard—but Possible

Not every town faded when its original industry declined. Some found ways to adapt, often by using skills and infrastructure already in place.

Greenville: From Timber to Manufacturing

Greenville began as a logging settlement. Timber drove its early economy, as it did across much of Michigan. When the forests were cut and mills closed, Greenville faced the same question as dozens of similar towns: what comes next?

Instead of shrinking into irrelevance, Greenville shifted. Its workforce had mechanical skills. Rail access already existed. Manufacturers moved in. Refrigerator production, truck manufacturing, and later wartime glider construction gave the town a second economic life.

During World War II, Greenville factories contributed directly to the war effort. That pivot did not happen by accident. It required investment, retraining, and a willingness to abandon the past.

Related reading:

The Extraordinary History of Greenville Michigan (1900–1950)

Key point: A town’s most valuable asset is not its original resource. It is its people.

Lesson Three: Survival After Disaster Is a Choice

Economic decline is only one test. Natural disasters have erased entire business districts and forced communities to decide whether rebuilding made sense at all.

Omer: Fire, Flood, and Persistence

Omer was once a busy lumber town. Fires repeatedly destroyed commercial areas. Floods wiped out homes and infrastructure. Each event could have ended the town’s story.

Instead, residents rebuilt—often knowing the next disaster was possible. The economy never fully returned to its early peak. The population declined. But the town endured.

That endurance was not driven by profit. It was driven by attachment, memory, and local commitment.

Related reading:

History of Omer Michigan – Fire, Flood, and a Small City That Endured Disaster (1866–1940)

Key point: Communities last because people decide they should.

The Long Decline: What Happens After the Factory Closes

When an industry leaves, the effects ripple outward:

Young workers move away.

Schools consolidate or close.

Property values stagnate.

Municipal budgets shrink.

These changes do not happen overnight. They unfold over decades. Many towns survive in a reduced form—smaller, older, quieter. Others find new identities tied to tourism, services, or regional commuting.

What they rarely regain is the economic simplicity of the boom years.

Why These Stories Matter Now

The loss of small-town industries is often framed as failure. That framing misses the point. These towns were responding rationally to the conditions of their time. They succeeded until the conditions changed.

Understanding this history matters for current debates about rural investment, manufacturing policy, and economic development. It also explains why promises to “bring jobs back” often fall flat. The industries that left did not disappear by accident. They were replaced by more efficient systems.

The lesson is not to recreate the past. It is to recognize the patterns.

Michigan as a National Case Study

Michigan’s experience is not unique. It is representative. The same cycles played out in Ohio steel towns, Pennsylvania coal communities, and Midwestern farming centers. Michigan simply offers a well-preserved record of how those cycles unfolded.

By examining specific towns and industries, the broader national story becomes clearer—and harder to oversimplify.

Where the Real Strength Lies

Factories can close. Mills can burn. Crops can lose value. What remains is institutional memory: how a town adapts, what it keeps, and what it lets go.

Some communities vanish. Others persist at a smaller scale. A few reinvent themselves entirely. None does it without cost.

Continue the Series

Thumbwind’s Michigan Moments project documents these stories town by town, using original research, historic photos, and long-form reporting.